I ordered something from a local business and the owner - a new immigrant from Detroit - brought it over to the house. As usual in this kind of meeting, I went into genealogy mode and asked him about his background. Where his family was from? And where before that? You know how it goes.

When I explained that I am a genealogy researcher, he told me that he had a problem that perhaps I could help with. He had a ketubah (=marriage contract) for an ancestral couple which adds the word "Halevi" to two mentions of the groom's name. The problem is that his family has no knowledge of coming from Levite stock. He acknowledged that this tradition may have been lost during a couple of generations of non-observance.

Still, he wanted to know as Leviim have certain perqs like being called second to the Torah. Symbolic, to be sure, but still.

I pointed out to him that it is not all symbolic. A Levite family is exempt from the commandment to redeem the first-born son. That is the case if the mother is the Levi, not just the father. Since this is a Torah commandment, he would do it even if in doubt, but a thinking rabbi, knowing the background, might have him do it without the blessing in order to avoid the "name in vain" business.

"Well," he said, "I am a first born and I know for a fact that I was redeemed."

So maybe that itself is enough to settle the question - unless of course he wants to do (or to commission) some more serious research. But the question in his mind remained, how could the error have occured to begin with.

So I countered with my own story. Well, not exactly my own, but the parents of my wife's late husband.

|

| The wedding took place in 1949, under the auspices of the Tel Aviv rabbinate. |

The bride's's father is correctly called "Halevi" both times his name appears (marked in blue) and though that may be the source of the confusion, it certainly doesn't excuse it.

The groom, who was a Hebrew-speaking, synagogue-attending man, added his signature at the bottom (see the purple arrow). How did he not notice the error? I mean, it has to be wrong, no?

I did the due diligence and inquired among other people with the same rare surname (including one who was in my high school class, who sent me to his father's cousin who was in my aunt's class), but none of them know anything one way or the other, about their own status.

Stone

The phrase "hewn in stone" implies both permanence and authority, the latter perhaps based on the Ten Commandments.

We know that gravestones deteriorate over time, but there are also occasions where they are wrong to begin with. In one case I know personally, the widow made an error of over three months in the deceased husband's birth date.

Here is the footstone of a family member, who was born in August 1901.

The date is correct, but she was not forty-five. She was about a week past her forty-fourth birthday. I took this photograph twenty-some years after the burial, so they had had plenty of time to fix it. I am told that the stone was eventually replaced but have not seen a photograph of the new one.

Another problem with a date is this.

The date of death is the twenty-eighth of Shevat, not the twenty-eighth of First Adar. The Gregorian date is correct as is the date of birth. (Additionally, his father is Moshe Menahem, not Moshe as it appears here, and his mother is Devorah Rachel, not Rachel. But his two daughters may not have known that. And they certainly didn't ask me.)

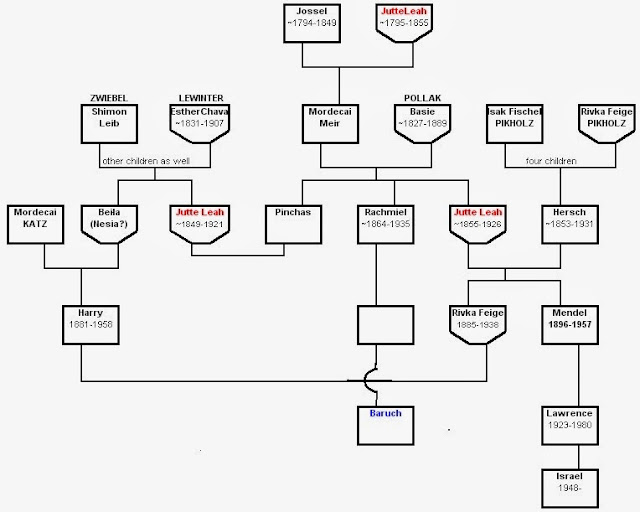

Another oddity, this from the Pikholz Project.

It shows her name as "Olga, wife of Avraham." (It does not mention her father, Berisch.)

And here is her husband, "Matityah the son of Avraham."

Olga's stone misidentifies her husband, using her father-in-law's name by mistake. She had one living son at the time of her death.

People really have to check this kind of thing. And we genealogists need to be sure of our facts, not simply depend on what is written, whether on paper, on stone, or in any other medium.