ביום חמישי

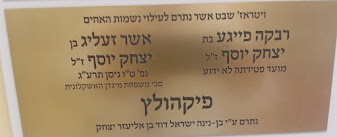

האחרון, כ"א באדר (20 במרץ), הקדשנו ויטרז' של שבט אשר בבית כנסת ברנע באשקלון לזכר אמא

של סבא רבא שלי רבקה פייגע פיקהולץ ואחיה אשר זעליג

.

להלן דברי בהקדשה.

(יש גם תרגום לאנגלית.)

תודה לכלכם שבאתם. גם אם לא לגמרי היבנתם מה הענין. כוונתי כרגע שתהינו,

גם אם לא תקלטו את כל הפרטים. הנושא המשפחתי מורכב אך לא יהיה מבחן. העיקר ההתרשמות

והרשם. והמסקנות. ולמה אנחנו במקום הזה במועד הזה.

לפני כמה עשרות שנים, שהתחלתי להתענין בהיסטוריה המשפחתית, אבי ספר לי

שֶלְסָבִיו, הרש פיקהולץ, היה דוד בשם זעליג פיקהולץ. מעבר לזה הוא לא ידע.

אבא נולד בארה"ב וגם סבא הגיע כילד בן שבע – כך שלא היה זכרון

משפחתי לגבי מָה – ומי – היה באירופה.

המקומות סקאלאט, זלושצ'ה, פודקמין ואפילו טרנופול לא היו מוכרים לאבא כלל

וכלל. אבל היה ברור שהיתה חשיבות לקיום הדוד זעליג, מבין כל הדודים.

כאשר התחלתי לפני כשלשים שנה להכנס ברצינות למחקר המשפחתי, סבתא ספרה

לי שלאמא של סבא רבא הרש פיקהולץ קראו רבקה פייגע. (את שם אביו כבר ידעתי מהמצבה.) השם רבקה פייגע

היה מוכר לי כי לסבי היתה אחות רבקה פייגע שנפטרה כעשר שנים לפני שנולדתי והיום היארצייט

שלה, זו הסיבה שקבעתי את המועד לארוע זה. הרי לא ידעתי מתי נפטרה הסבתא רבקה פייגע

– לא שנה, ולא תאריך. אפילו לא העשור. ידעתי רק שהיא נפטרה לפני שנולדה האחות של

סבא, דודה בקי, בשנת 1885. זה גם לא נראה לי חשוב במיוחד.

עם קידום המחקר ובסיוע דנ"א, גליתי ששני הוריו של סבא רבא הרש

פיקהולץ היו פיקהולץ – בני דודים בצורה זו או אחרת. ושדוד זעליג היה האח של אמו

רבקה פייגע ולא של אביו. שני האחים - רבקה

פייגע וזעליג היו שנים מילדי יצחק יוסף פיקהולץ (שהיה ידוע בפי כולם בשם יוסף)

ואשתו רוזה (עליה לא ידוע דבר, גם היום).

כאשר כלים חדשים נכנסו למערכות המחקר – ארכיונים באינטרנט, בדיקות

דנ"א ועוד – למדתי שרבקה פייגע היתה תחילה נשואה לאיש בשם גבריאל (שם משפחתו

לא ידוע) ושנולדו להם שתי בנות בריינה ושרה בסביבות 1840. גבריאל נפטר ושדכו אותה

עם בן דוד ממשפחת פיקהולץ (כפי שהיה מקובל במקרים של אלמנות או אלמנים עם ילדים

קטנים). כך נולדו לה עוד ארבעה ילדים שהקטן סבא רבא שלנו צבי הרש, כנראה בשנת

1853.

בריינה – הבת הראשונה מנשואי רבקה פייגע עם גבריאל – נשאה לאברהם אהרן

ריס משם יצאו כמה דמויות ידועות, ביניהם פרופסור אגון ריס, קרדיולוג בעל שם שעבד

שנים רבות בבית חולים רמב"ם בחיפה וקודם היה רופא העיר העתיקה בירושלים של

תש"ח.

שרה – הבת השניה מגבריאל – נשאה ליצחק באאר ועברו לצכיה ומשם לארצות

שונות – רק לא לארץ ישראל. אני בקשר עם צאצאים של שתי הבנות היום. אבל משחשוב

לעניננו, שתי הבנות בריינה ושרה נתנו את השם רבקה לבנותיהן הבכירות. מזה הסקתי שרבקה

פייגע הסבתא נפטרה לא אחרי 1862, כשהרש, הסבא רבא שלנו, היה לא יותר מבן תשע.

ואולי אף צעיר יותר.

וזאת המפתח לכל התעלומה. מי גדל את הילדים היתומים? לא אחר מהדוד

זעליג ואשתו חנה. לא חשוב כרגע איך סגרתי את הפינות. המסקנה ברורה וחד משמעית. הילדים

שנולדו וחיו בפודקמין עברו לדוד זעליג בסקאלאט, מקום לידתה של רבקה פייגע. שנים מילדיה אף התחתנו עם בני סקאלאט.

זו הסיבה ששמו של הדוד זעליג היה חשוב עד כדי שאבא שלי שמע עליו.

הדוד זעליג, דרך אגב, נפטר בט"ו בניסן

תרע"ג (1913) בגיל 83. ארבעים שנה אחרי אשתו חנה, שהיתה שותפה עד מותה לגידול

הילדים של רבקה פייגע. אנשים עושים מחקר משפחתי מסיבות שונות ולפעמים ללא

סיבה בכלל. אני הרגשתי דחף פנימי לתעד את המשפחה מאז הייתי ילד. ועכשיו אני מבין. זה

היה היעוד שלי. אנו, כל המשפחה שלנו, חייבים חוב גדול לדוד זעליג על החסד שעשה

לאחותו וילדיה ונפל בחלקי לגלות זאת ולהכיר בכך לעיני כולם במקום זה היום, כפי

שמשתקף בארוע הזה ממש. ועל זאת עוד אפרט.

והנה ספור. בשלב מוקדם במחקר שלי, לפני כעשרים וחמש שנה, קבלתי רשימה

של כל הפיקהולץ הקבורים בבית הקברות בוינה. חלק הכרתי, חלק לא. במשך הזמן, קבלתי

צלומים של המצבות אבל אלה לא תמיד עזרו. חלק מהמצבות נראו לי חלקות לגמרי, ללא כל

כיתוב. ביניהם אחד בשם מאיר פיקהולץ שנפטר בשנות הארבעים לחייו בשנת 1916. אשתו,

לרה, נפטרה כשנתיים וחצי אחריו.

הרגשתי קשר בלתי מוסבר לאותו מאיר פיקהולץ וגם מצאתי תכתובת בין בתו

יחידתו (שהיתה אז באיטליה) לבין מוסדות העליה אך לא יכלו לסייע לה והיא נספתה,

כנראה באושוויץ.

לפני שבע וחצי שנים נסעתי להונגריה עם בת דודה שלי מארה"ב וביום

האחרון עשינו בוינה. ואני הלכתי לבית העלמין האדיר עם רשימת קברים משפחתיים בידי,

כולל שבעה בני דודים ממשפחת ריס. לקראת הסוף, מצאתי את מאיר והמצבה אכן נראתה

חלקה. הצלחתי בכל זאת לחשוף את סודותיה של

המצבה והנה ר' מאיר פיקהאלץ בן ר' אשר זעליג מטארנאפאל. מאיר. בן דוד ראשון של סבא רבא שלי. ושם המלא של אביו, אשר זעליג.

והמצבה ממשיכה "נפטר בתוך הגולה פה ויען." מצלצל ממש כמו

הפסוק הראשון בספר יחזקאל "ואני בתוך הגולה על נהר כבר."

כיתוב של יהודי ציוני.

משוכנע אני שאלו היה עובר את מלחמת העולם הראשונה היה חי את שארית

חייו כאן בארץ. והקשר שלי עם משפחת הדוד זעליג רק מתעמק.

|

| עם בן-דודי גיל, בן-נינו של הדוד זעליג |

אבל זה עוד לא הסוף. לפני עשרים שנה,

מצאתי, כפי שהזכרתי, את הקבר של זיגמונד מיגדן, הנין של הדוד זעליג. ליד זיגמונד קבור אחיו, מאיר שנולד ב-1916 סמוך

לאחר פטירת דודו מאיר בוינה. ופגשתי את בנו של זיגמונד שידע לספר ששמו של זיגמונד,

בעצם אשר זעליג.

וקברים אלה בחלקת "אדיבי" ליד בית העלמין הישן כאן באשקלון.

בבית קברות פרטי שהיה בתוך פרדס. פרדס שכבר איננו, אבל עוד היה כשבקרתי לראשונה.

מישהו עוד רוצה לשאול איך נרקם הארוע הזה להנצחת רבקה פייגע ואחיה

הדוד זעליג, כאן באשקלון? לקדוש ב"ה יש דרכים משלו.